The Argument Against AI Image Generation

A typical argument one comes across from those in the anti-AI image generation camp goes something like: “AI image generation steals art from artists putting them out of a job; and what it produces can’t even be properly considered art anyway.” To analyse this stance properly, it must be broken into its constituent parts:

- AI image generators should be opposed because they steal art from artists;

- AI image generators should be opposed because they put artists out of their jobs, and;

- images produced by an AI do not count as art.

Do AI Image Generators Steal From Artists?

On The Impossibility of Stealing an Idea

So, do AI image generators steal art from artists? The short answer is: no, they do not. Theft is a very specific legal concept, it refers to the unjust re-distribution of property from party $A$ to party $B$. The important part of this is that property rights can be held only in scarce means—the issue with Bob stealing Alice’s car is that this deprives Alice of that car. Bob’s use of the car is incompatible with Alice’s use—this is what theft refers to. Artistic ideas, like any other idea, are simply not scarce—Bob is capable of looking over Alice’s shoulder and painting exactly what she is painting without depriving her of anything that she owns. The correct terminology to describe some rule which would prohibit Bob from doing this is a negative easement—not theft.

Do AI Image Generators Plagiarise?

AI Image Generation as “Filling in the Gaps”

So for the issue of digital image creation, there is nothing that is or can be stolen from an artist, nobody is deprived of any scarce goods when someone copies the ones and zeroes that define such digital artworks. There is a second aspect of this to address though, perhaps the AI image generators aren’t literally stealing anything in the legal sense, but rather are plagiarising from artists, or some other similar concept. It could well be that nobodies rights are violated by the use of an AI that is trained on a bank of digital artwork, but said use might be immoral still. To address this point, allow me to briefly go over how these AI image generation algorithms work, specifically focusing on those models such as Dall-E and Stable Diffusion.

Very simply, the core of such algorithms is a de-noiser—you have an image with some amount of noise, and you ask the algorithm to predict what noise has been added to that image, such that you may subtract it. Conceptually, this makes sense when you consider what it means to remove noise. If I have a picture of an aeroplane, and there is noise covering up the left wing, to remove that noise is to “fill in the gaps.” It is working out what is missing from an image. So, if you have a computer program that fills in the gaps like this, then give it an image of pure noise and ask it to get rid of this noise, you have given it in essence a blank canvas—you have asked it to fill in the gaps and given it only gaps.

I would put it to you, dear viewer, that this is essentially how human artists learn to draw pictures as well. A human has various visual filters in their brain that can be used to pick out features in the objects of perception, then the human is able to classify different sets of features into different concepts. A human learns which visual features are present in, say, a hot dog or a spaceship. The AI does a very similar thing—it is trained on a bank of pre-classified images, invents various random filters for those images, learns which features are picked out by those random filters, and then learns which features correspond to the concept “hot dog.” If I want to draw a picture of an orc, but have never seen nor heard of an orc before, so I look online at previous pictures of orcs, what I am doing is learning how to fill in the gaps. I figure out what an orc face is, then I can draw one, I figure out what an orc sword looks like, then I can draw one, and so on until the entire blank canvas is filled.

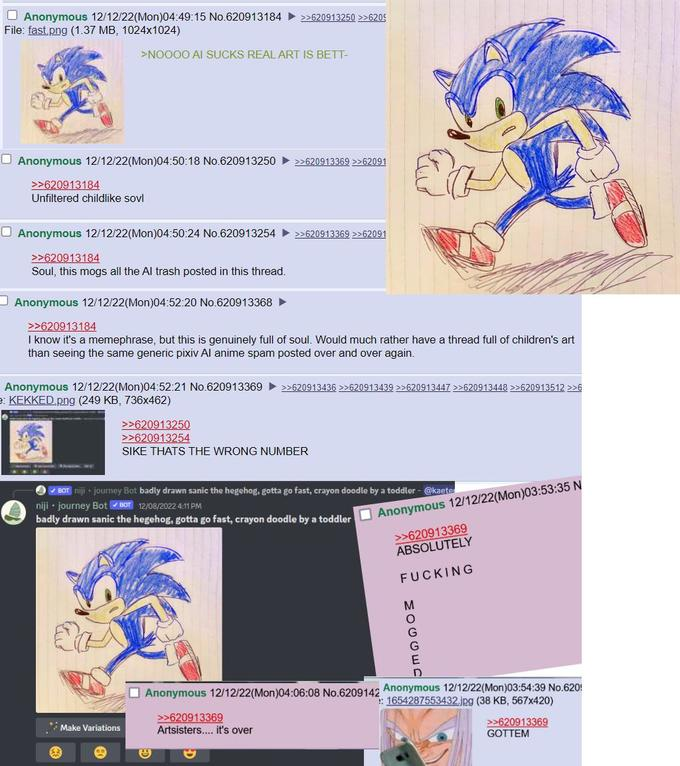

Art YouTuber, Ethan Becker, seemingly agrees with me here. In his video explaining how to find your artistic style, the method provided is to pull out different aspects from different works of art, and then combine them to make a new piece.1 This “style-bashing” as one might term it, is evidently an accepted technique within the artistic community when done by human artists—and yet when it comes to an AI doing this same thing it is painted as a clear-cut case of plagiarism.

AI Image Generation is not Photo-Bashing

This brings me to the point of discussion, namely the claim that AI image generators plagiarise the work of artists. To clarify some confusion which leads people to believe this, these AI image generators do not inherently work as “collage” or composition software, or in the words of the Concept Art Association’s Karla Ortiz that “the software […] breaks down all of the data [that was] gathered and shreds it apart into little […] bits of noise, and […] it starts grabbing little bits of shredded data from all over the place and […] slowly re-integrates it to pretty much create a new image.”2

So to be abundantly clear: these AI systems do not store the images used for training and blend these images together. All that is stored by such models is the set of weights which define the technique for going from noise to image—in other words all the model stores is the method used to fill in the blanks, which is exactly what is stored in the brain of a human artist. For a program to operate in the way suggested, where new images are generated by stitching together many previous images, would require that the entire bank of training data be stored somewhere—in other words a model like Dall-E or MidJourney would need to store the many terabytes of images they were trained on and be able to query this database in realtime. This would be reflected in the size of such a model—it would be several hundred-terabytes large, rather than a few gigabytes.

So, the calls that the model somehow tell artists which images it was referencing to make some new generation are flawed to their core—the AI is not referencing specific images and combining different aspects, it doesn’t have any access to it’s training set. Now, the obvious response to this point, which I will address more fully later, is that of over-fitting—over-fitting is a real thing that happens, but it is not at all the expected behaviour of such a system, and it also does not demonstrate that the expected output of such a system is in any way a form of photo-bashing. Like, just from a pure data perspective all that is stored are the weights of the neural network, think of these like the paramaters in some linear equation, you tweak the paramaters until your output is matching what you would expect. [NOTE: this is a massive over-simplification of how neural networks work, but it’s accurate in the relevant ways]. So, the only place where an image generation model could possibly store some representation of its training data is in these paramaters. Stable Diffusion XL has 2.6 billion such parameters3 and the LAION-5B dataset which everyone is so concerned about contains 5.86 billion images, which comes out to about 240TB, which means you have less than one paramater for every two images, or in other words if we assume each parameter is stored as 32 bits which is standard for most number operations on a computer, then you have roughly 0.00004 bits of paramater data for every bit of training data—to store the training set in the model you would need at least 1 bit of paramater data for every bit of training data, or in this case you would need about 25000 times the number of paramaters, which would be 65 TRILLION paramaters.

Now, 2.6 billion and 65 trillion are both gargantuan numbers, and it can be challenging to immediately get how much bigger one is than the other, so I think a visualisation is in order. Imagine if I took a three-week old kitten and placed it on a scale, then on the other side I drop a fully grown African elephant bull—the world’s largest land animal. The difference in weight between this tiny kitten and this monstrous elephant would be roughly equivalent4 to the difference in paramater count between Stable Diffusion XL and our 65 trillion-paramater model required to reach the bare minimum for general over-fitting. I think this makes clear why any suggestion that the general output from such models is over-fitted or collage-work or photo-bashed is simply ludicrous and could not be the case.

Bear this point in mind, people like the anti-AI golden boy, Steven Zapata, will tell us that “machines can replicate references exactly.”5 This is an argumentative sleight-of-hand. Sure, machines can indeed create exact duplicates of data—but this is not what the argument is about. Artists are not opposed to your computer making a copy of their pictures when you navigate to their ArtStation page—this copying is required in order for you to see their art in the first place. Rather, the argument is over whether AI image generators make exact replicas of their training data—and the answer is a resounding “no.” AI image generation is not collage, AI image generation is not photo-bashing, AI image generation is not copying—these tasks are all fundamentally different to the de-noising process that is performed by a diffusion model. The task of copying data from one location to another is a task that was solved by computer scientists decades before anyone even thought of trying to get a computer to produce images, and it is a task that makes the Internet that we are having this argument over possible in the first place.

Zapata is not alone in this deception, Mother’s Basement attempts to draw a disanalogy between machine and human learning by this same method:

Humans cannot perfectly reproduce the work of other humans without tracing over it or using a mould or stencil. Inevitably in the process of trying to do so, any human artist will end up applying their own creative interpretation to the style that they’re aping based on their own unique experiences studying other peoples art, developing their own artistic techniques, and just living life.6

This exact same thing is true of AI image generators—to make this analogy precise, the act of using a mould or stencil would be what is analogous to the image-to-image technique. This is a very specific function of these AI tools, and it can indeed be used to plagiarise artists—Mother’s Basement conflates all possible uses of diffusion with this one very specific practice and insodoing throws the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. When the human artist is “aping” someone’s style, it involves “their own creative interpretation” “based on their […] experiences studying other peoples art”—notice how this description is contrasted with the AI “blending together” or “collaging” other works that it has been trained on. When a human does it, it’s just applying their own unique spin based on works they have studied, when an AI does it, it’s plagiarism of every single work that has ever touched it’s training set.7

In fact, an artist by the name of Jazza paid $1200 to fiverr artists to produce artwork based on the same prompts that he gave to Dall-E and over half of what he spent went to people blatantly and actually photo-bashing with stock images found on Google.8 This is in heavy contrast to the text-to-image AI which is fundamentally incapable of photobashing Google image search results. If this is the quality of work that is to be expected from commissioning human artists, can you really blame people for turning to AI? If human artists are to put forward this level of incompetence for these prices I fail to see why I should shed a tear for their loss of income---these are the artists who are going to be out of a job, not those who actually put the fucking work in.

Even opponents of AI image generation can’t help but to implicitly admit that these systems do not work by photo-bashing, Hello Future Me tells us that AI art is “entirely disconnected [and] in no way highlights or preserves the original work,”9 but then within that very same video he raises the ethical (and legal) concern that “AI art is theft.”10 But, which is it? If the AI-generated images are “entirely disconnected” from their training data then surely they couldn’t be either theft or plagiarism. The anti-AI crowd like to eat their cake and have it too on this issue: AI art is both soulless and orthogonal to anything that a human would produce, and it is based entirely in plagiarising and stealing the art of humans. They have not quite landed on which argument they want to make—do they want to make fun of how low-quality and devoid of meaning it is, or do they want to make the argument that these AI systems produce art of impeccable standards, ripped straight out of the hands of the lowly painter, who is now entirely incapable of getting a job due to the vast enormity of the tyranny of the machines? They can’t decide, so they just do both—that surely won’t lead to any naked inconsistencies, right?

Where AI Does Plagiarise

Now, is it possible for a person to use these AI image generators to plagiarise art? Certainly. Just as it is possible for a human to do so. But, the mere fact that an AI has learned to fill in the gaps using previously produced artworks is not sufficient to demonstrate that such plagiarism has occurred. There are certain features that must be present in any depiction of an orc that both humans and AIs must learn and utilise in their own depictions. That you must look to previous depictions of orcs to learn these features is simply a comment on how knowledge is acquired in the first place. Learning which features show up in orc pictures is not the same as plagiarising said pictures.

Shadiversity points out11 that the examples commonly cited to show AI image generation plagiarising do not use the text to image technique, but rather are analogous to applying filters to an already existing image, called image to image. Certainly, it is possible to plagiarise art with this technique, just as it is possible to plagiarise art by tracing over an existing piece in photoshop—but that does not make photoshop, or even tracing per se tools of plagiarism. Moreover, any claim of plagiarism must be specific—it is not sufficient to assert “maybe someone somewhere out there has at some point generated a piece of art that plagiarises from me.” If you are to claim that AI art is plagiarised you must link a specific piece of AI generated art to the specific piece of art that it plagiarises. These non-specific claims must be discarded on their face as epistemic null-statements—a claim of plagiarism presented without evidence may be dismissed without evidence.

Which Aspect is Plagiarised?

Moreover, which specific aspect of your work was plagiarised? Adam Duff of LUCIDPIXUL concurs with me that the AI is not photo-bashing, but is rather learning the process to create art:

[…] you mentioned as well, to kind of segue into the next thing I wanted to mention, […] which was: […] what’s the part of our art that’s being stolen from us? Right? If you’re watching a bunch of people who’ve never drawn anything before in their life, they’ve never trained [themselves] in artistic fundamentals, and we’re watching them. I’m on MidJourney and I’m watching a bunch of people prompt different images–painted or photographic or whatever […]–you’re watching people prompt this out and you’re thinking to yourself: “what is it about that that would be hurtful or bothersome or worrysome to a trained artist?” […] What are they taking—what are they taking for granted? And that is the process. […] It’s the artistic process–the fundamentals–it’s this sacrifice of time and energy—we, as people, at least in society as we’ve known for a very long time, […] [have] been valued, our skill in general […] is based off of how our ability to do something that someone else can’t or isn’t willing to do. It’s our craft, it’s the time and energy that we put into it, and all of a sudden that’s taken away from us, right?12

This is, of course, a slip of the mask—or perhaps a motte-and-bailey approach to the argument. The weaker bailey being the stance that AI is actually photobashing or in some other way plagiarising specific components of peoples artwork, which is then abandoned to fall back to the far stronger motte of AI simply learning to emulate the process that humans take to make unique pieces of art. Now, if this motte is supposed to indeed be defending the stance that AI image generators plagiarise–or in the words of Adam, “steal”–the art of human artists, then am I to accept the stance that it is plagiarism for anyone to implement the same style as another artist in the making of an entirely different piece? This would surely be a very hardline stance, and not one that I am aware of any artist taking up, unless perhaps there is some Galambosian13 art collective out there that refuses to paint anything without first compensating the descendants of some random caveman.

This stance would mean the total death of any creativity, lest one be accused of plagiarism and theft. “I’m sorry, van Gogh, you want to do your own take on The Sower? Tough luck, sunshine. Jean-François Millet owns that concept.” “What’s that budding artist? You want to follow along with Bob Ross as he paints that cabin? You are literally Satan, none of that.”

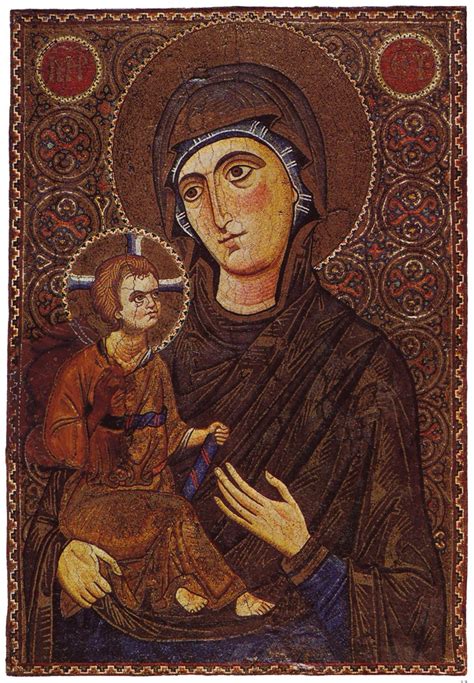

vs. by Vincent Van Gogh (right)“)

So, far from AI art meaning a killing blow human expression, what Zapata and his fellow AI worriers should be concerned about is the nonsense proposals from their own side that the method of artistic expression be somehow protected as a monopoly of the first man to discover it.

Analogy to AI Image Classification

On this point of plagiarism, we can take an analogy from AI image classification. If I train an AI on many millions of pictures and then hand it a new image and it tells me that there is a 93% chance that the image I showed it was a plane, has this AI “stolen” the identification of percepts from humans? It is certainly true that a human must have at some point gone through the work of identifying many pictures of planes, but this does not demonstrate that this ability was stolen from them or plagiarised from them by anyone who looks at their work to figure out what a plane is.

Zapata on the Disanalogy Between Human and AI Art

His Argument

Zapata opposes this analogy between AI and human learning, claiming on the Art Cafe podcast that AI systems learn in a categorically different way to humans:

I just wanna remind people–and again, this is more philosophical–but its like: when something like Stable Diffusion is trained, it’s locked in place, which is unlike human learning, right? We’re always adapting, transforming, our moods effect everything---Stable Diffusion is just: it is what it is, as it was output, […] and it’s going to, if you give it the same prompt and the same random seed on any given day, it will produce the exact same output image. […] There’s nothing stopping someone from just running all of Stable Diffusion and outputting every possible image it can make except for an impossibly huge electricity bill—that’s the only thing that’s stopping someone.

So in a very real sense, […] when you are interacting with one of these systems, you are mining—you’re going in and you’re trying to locate yourself using the prompts within a space that is already defined, it’s already objective. It’s […] like those pieces of gold are already in the river and the people who are prompting are sifting for gold, and there’s a lot of fools-gold and they’re throwing it around. […] It’s not generating unique things every time that you prompt—when they shipped Stable Diffusion it was done.14

[…]

All of that is just me riffing a little bit on this–what I consider–[very] erroneous and spurious argument that these things learn the way we do. It’s like for that to be the case you need to assume that consciousness and self-awareness have nothing to do with learning which is like: I don’t assume that! I think that the fact that there’s someone here to learn is vital to the act of learning—there’s nothing there to learn anything in these programs. I don’t think the learning they are doing is learning as we are familiar with it at all, I don’t think that makes any sense.

[HOST]: Until I hear that there [are] general artificial intelligence algorithms out and working I would never trust this argument to be honest.15

[…]

If somebody said: “ok this is an actual conscious robot,” then all of those arguments are on the table, but that’s also the same day that I’m not talking about art.16

Steven’s argument here may be broken up into two parts:

- AI image generators don’t learn to produce art because upon the completion of training they are deterministic with respect to the mapping between input and output, and;

- AI image generators don’t learn because they are not general intelligences.

“AI image generators don’t learn to produce art because the Latent Space is Deterministic”

On this first argument, I simply do not see how exactly this refutes the point that they are learning—surely it is commonly understood that any learning these systems perform would be done during the training stage of their production, not once the model has already been trained. Analysing whether a pre-trained model is capable of continuing learning is completely irrelevant to the question of whether a computer program can in principle learn, and also as to whether these specific programs learn. That the mapping between input and output is set in stone at any given stage of learning does not negate that learning has occurred. Now, it certainly is true that these programs are not identical to humans in their capacity for learning–humans possess free will after all–but lacking free will is a feature of any non-conceptual consciousness. Dogs are not generally understood to be conceptual beings–beings with reason–and yet they can definitely learn a trick or two.

Moreover, Steven is falling into the classic error in philosophy, where he conflates the potential with the actual.17 The latent space is a mathematical description of every potential image that can be generated by a given model, these images are not actualised until said generation has actually occurred. This is the exact error committed when people use Zeno’s Paradox to disprove the possibility of motion: the idea is that to move from A to B, you must first move half the distance, and to move half the distance you must move a quarter, and so on ad infinitum. Therefore, they say, it is impossible for anything to go anywhere. What this amounts to is saying, “hey, I can continually subdivide this line forever,” which is true, but this is describing a potential—I have the potential to keep listing off smaller and smaller fractions, but said fractions are not actual unless and until I actually get to them during my listing.

We can analogise the latent space here, to the library of babel, which is a website that hosts a mathematical model which has mapped out every possible string of text of 3200 characters. Does this mean that whenever anyone types or says anything, all they are doing is pointing to a location in the library of babel, thus proving that their thought was unorignal and that they cannot learn? Surely not. I can tell you that the introduction to Zapata’s video is written verbatim on page 82 of volume 3, on shelf 3, of wall 1 of hexagon 17esdrawgcz... etc.18 That I can point to a mathematical description of Zapata’s video does nothing to demonstrate that said video actually existed prior to him making it.

The Analogy to Photography

Further, even if the latent space was actual, that in order for the model to function it had to literally go through the process of generating every possible image, this would still not make AI image generation plagiarism, nor would it negate the artistic worth of such generation. Surrealist19 artist Miles Johnston analogises such an actual latent space to photography:

I’m almost starting to see generative art as more analogous to photography, where the latent space[,] […] you know the space of possible images, is almost a feature of the natural landscape and these are different ways of going in and finding imagery from it. In the same way photography–you know you can take a lot of crappy photos–but people have over […] its lifetime, raised it to a degree of artistry that is, at this point, I think you would have to be a bit of a nut to not respect—but it’s not hard to find artists who were extremely threatened by it.20

Now, the obvious attempt to draw a disanalogy here would be to point to the fact that the AI image generators can produce their artworks only on the backs of previously made human art. This does not break the analogy, however, as there exists a certain subset of photography that is of things which have been shaped by the hands of men. Does a photographer lose his artistic credentials for photographing a forest where the trees were shaped by medieval loggers?21 If you photograph a moor are you plagiarising the bronze-age farmers who made it that way? Is it that everyone who has photographed a skyline has in some way wronged the architects of each of the buildings that make it up? Certainly not, that a physical landscape was shaped by man does not make it non-art to photograph it, and the same applies to an actual latent space.

Steven elsewhere criticises the analogising of AI image generation to photography:

Maybe this is kind of tied to how I view […] the appeal to history of like, “oh well, what about when photography came along with oil painting?” So, the reason why I am not compelled by that comparison is that photography and oil painting were parallel and independent technologies. So what do I mean by that? I mean that we can imagine photography having been invented if oil painting had never been invented. Right? There’s nothing about oil painting that actually intersects with photography—if it had never occurred to anyone to create images with oil paint, photography might have still occurred to somebody. So I consider them completely parallel and independent technologies. So, there was no scientist taking cameras into oil galleries and photographing the paintings on the walls in order to produce cameras.22

Now, Steven has indeed pointed to a legitimate difference between photography and AI image generation, but, again, what needs to be kept in mind is whether this is a relevant difference. In attempting to show the disanalogy between $A$ and $B$, it is not sufficient to point to some aspect that they do not share, you also need to show that said aspect is central to the point being made. So, what exactly is it that people are saying when they bring up this point of photography? We have seen at least one example of this from Miles Johnston above, and in that instance, Miles was relying on the pre-existence of the latent space being analogous to the pre-existence of some physical landscape that one photographs—the point being that said pre-existence does not negate that capturing it, or “mining it out,” is still a legitimate form of art.

However, this is not the only way this analogy is employed, and I do not believe it is the way that Steven is getting at here in particular. So, another argument that I see this analogy used to support is in response to artists complaining about job losses from AI, a typical exchange might go as follows:

[ARTIST]: The use of AI image generation to produce works of art is immoral because it puts artists like me out of a job.23

[AI PROMPTER]: Well, the same can be said of photography—that put many oil painters out of their jobs, but now there is a whole new art form which came out of that.

Here, the similar aspect which the analogy rests upon is clearly that the new method of art production makes it harder to profit on older methods. This is clearly true, and Steven agrees with me on this point that photography put oil painters out of their job, which would make the analogy stand. So if I am to be charitable to him, then I am forced to assume that he is not responding to that specific usage of the analogy, but I am running out of ways to apply this argument. Steven has said multiple times across multiple videos that he is disinterested in the argument over whether AI art is art, so it isn’t that, but there is very little left: it’s not about job losses, it’s not about AI being plagiarism because it is built on the backs of human artists, and it’s also not about AI image generation not being art. Perhaps I have missed some extra argument that this analogy is employed within, but I certainly can’t see one within what Zapata says. From what I can see, either his drawing of a disanalogy fails, or he has not actually done said drawing—either way his argument falls.

“AI image generators don’t learn because they are not general intelligences”

So, now I may move onto Zapata’s second point, that AI image generators don’t learn because they are not general intelligences. This is simply nonsensical—what is a general intelligence if not one that learns generally? That we need a modifier term to identify general learning surely indicates that there is such a thing as non-general learning, i.e. learning done about some specific endeavour. That something does not learn generally does not show that it does not learn, it may well be the case that it learns only about one specific area and no others. This is certainly true for image generation models: they learn how to perform the specific task of removing noise from images. Specific learning is learning: A is A.

Solar Sands on the Disanalogy Between Human and AI Art

His Argument

Solar Sands has an alternative thesis as to why Humans and AI are disanalogous when it comes to the collection of references:

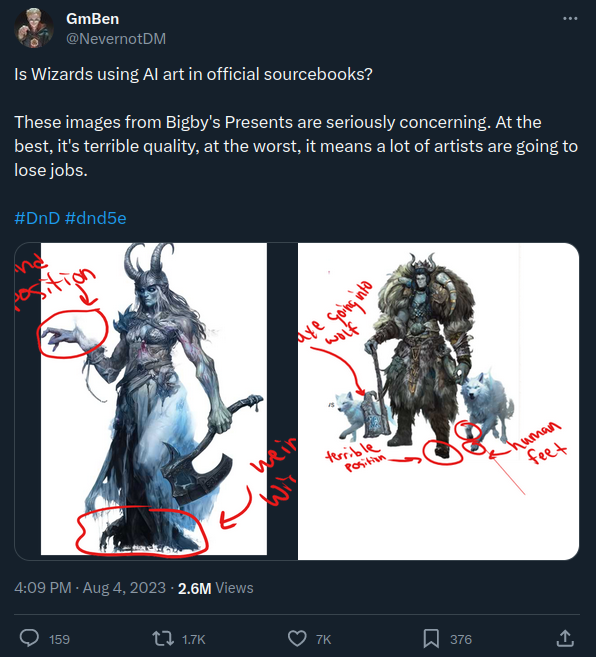

The process of AI art generation, from what I gathered, is more similar to the process of how a human artist operates than it is to a machine that has no capacity for spontaneity, but the systems at their core are still very different. For one, AI and individual artists work at vastly different scales. One artist in their entire lifetime would only be able to study a few-thousand images, whereas an AI would be looking at millions, if not billions, of images. The AI makes thousands of statistical calculations and weighs probabilities—it is not creative, nor is it “intelligent” in the same way a human mind is. AI may make mistakes we recognise as analogous to human mistakes, such as messing up hands—but it also makes mistakes that are completely stupid and no human would ever make. Like signing works with blended signatures, because that’s what paintings usually have, or misunderstanding how an object is constructed, so it can exist in a world with gravity. This is the difference between vast, unfathomable machines, controlled by for-profit companies and the incredibly limited referencing capabilities of your average human artist, who is unlikely to mimic the styles of thousands of artists and produce rip-off art in massive quantities to the point it could replace those artists from which they referenced.24

So, from that I can see two arguments:

- that AI is disanalogous to human artists because it references vastly more original works, and;

- that AI is disanalogous to human artists because it makes mistakes that a human would never make.

The Disanalogy by Scale

For his first argument, I simply fail to see why exactly the scale is at all relevant. To show there to be a disanalogy between $A$ and $B$ it is not sufficient to point to some difference, in this case the scale of operation, what must be shown is that there exists some principled difference. Solar Sands has seemingly neglected to undertake this task—the only thing I can see within his point here that could constitute elucidating a difference in principle is that humans are “unlikely to mimic the styles of thousands of artists and produce rip-off art in massive quantities to the point it could replace those artists from which they referenced.” So then is the principle that it is bad referencing when the referencer puts the referencee at risk of losing his job? Superior human artists are constantly putting each-other out of jobs, as is the case in every industry—if nobody else on planet Earth made any artwork, then I could quite easily swoop in and gain for myself a sizeable income. The failure of this sort of job-protectionism will be elaborated upon further into the video, but even without any of the information there, it seems absurd to suggest that John would be in some way wronging Kate by referencing her work because of the fact that he thereby increases the competition for artwork containing whatever aspect that he incorporated from her. If nobody after Tolkien were allowed to incorporate the fantasy elements that he came up with in future works, I’m sure his books may well have sold many more copies, but that does not establish any moral right for him to enforce a monopoly over those ideas. That is all to say, that any level of referencing from an artist thereby gives consumers more choices of which artist to commission to produce the referenced aspect—if only one artist on Earth is allowed to do cubism, then anyone who wants a cubist painting must go to him. Thus referencing by it’s very nature threatens other people’s jobs.

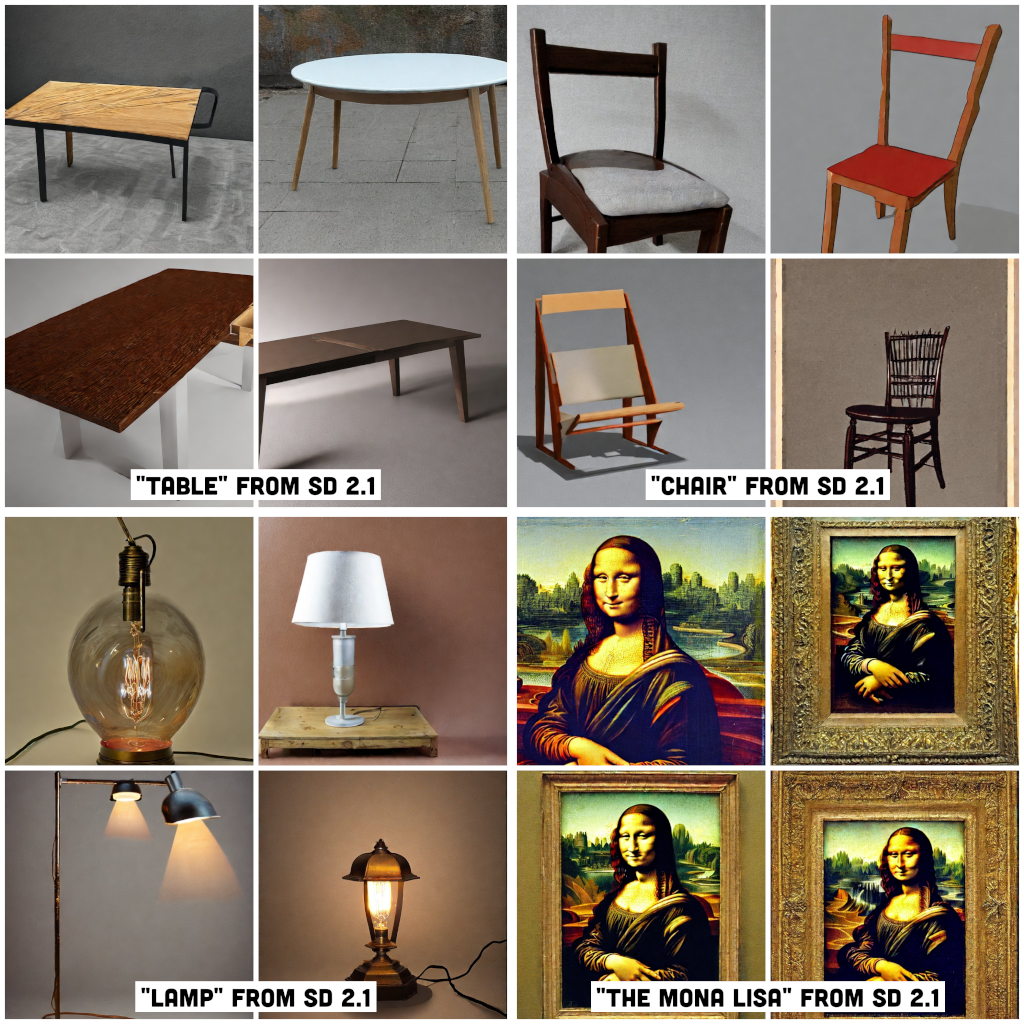

Moreover, Solar Sands seems to be vastly under-estimating just how much referencing your average human does—from the moment that we are born we are being hit with a constant stream of sensory information which we are able to rationally integrate into a wide array of concepts. Sure, most of the sense data that a human receives is not of art pieces, but the same is true of these AI training sets. Recall that these are text-to-image systems, not text-to-artwork—in general an AI image generator is far more adept at producing things such as “table,” “chair,” or “lamp” than it is at composing artistic masterworks.

The Disanalogy by Mistakes

Now for Solar’s second argument, namely that AI is disanalogous to human artists because it makes mistakes that a human would never make. On this point, he cites two examples:

- AI signing works with “blended signatures,” and;

- not understanding the correct composition of objects given the law of gravity.

I go over the signature example specifically later in this video when discussing over-fitting, but that detail is not required here in particular. The general principle behind these examples that Solar provides is that the AI does not understand certain things that humans understand, therefore it is using references in a fundamentally disanalogous fashion—and, again, Solar seems to have neglected the part of the argument where he shows why this is a relevant difference. Do the medieval artists who had no clue how to draw humans with correct anatomy also fall foul of this, or is it specifically that you don’t know what signatures or gravity are? It would strike me as the least charitable interpretation of what he is saying here to be that it is literally only those two mistakes that make the relevant distinction between man and machine, but in attempting to broaden the principle it leaves one with equally absurd outcomes. If bad referencing is whenever the referencer doesn’t understand some law of nature, not just gravity, then every human who has ever made any art is a bad referencer up until the point that we discover a theory of everything.

To steelman his point as best as I can, we can narrow the focus from not understanding just any law, to specifically not understanding those laws that are perceptually given to man without any aid from tools or instruments—the sort of law that would say “when you throw a rock it will go where you threw it,” or “fire is hot.” However, this is still a poor basis for any sort of ethical distinction between good and bad referencing—for how would this theory account for Martians or other aliens which might have completely different sensory apparatuses than us, and may require massive chains of deduction and experimentation to even know something as simple to us as the fact that light exists. Heck, we don’t even need to consider aliens here, there are a great many humans who have a condition called blindness who would lack any direct sensory perception of light—are these people therefore bad referencers because they don’t have direct and implicit knowledge of such phenomena and who therefore might make elementary mistakes with respect to its depiction? Surely not. What if there was someone who was severely mentally handicapped painting along with Bob Ross, would they become evil the moment they try to copy his motion of making a signature, assuming this individual had no understanding of what writing is or does? Such a statement would certainly strike most people as absurd, and yet it is the argument in its strongest form based on what is currently present in Solar’s video.

“There is Nothing it is Like to be Stable Diffusion”

Another point brought up in this discussion,25 in seeking to demonstrate a disanalogy between the way that humans and AI learn art, is in the assertion that there is nothing it is like to be Stable Diffusion, i.e. Stable Diffusion is not conscious, so therefore it must be doing things in a fundamentally disanalogous way to humans. On this point, I present to you ripgrep. ripgrep is a command line utility that allows you to recursively search through every file in a directory for a given string of text. I have here a directory with files representing the rooms of my house:

house/

├─ bedroom-1.csv

├─ bedroom-2.csv

├─ hallway.csv

├─ living-room.csv

├─ kitchen.csv

Each file contains a list of objects within that room, so if we look at what is in bedroom-1, we can see that I have a bed, a desk, and a computer (the file contains this string of text: bed,desk,computer). Imagine what I would do if I had lost my phone, and I wanted to search through each of these files to find the room where it is. Clearly what I would have to do is open up these files one at a time, and look through each item in the list that they contain, until I find an entry that says “phone.” I go about doing this and sure enough, it was in the living-room. I can accomplish the same thing by using ripgrep: what I do is I type rg phone, rg standing for ripgrep. And sure enough, ripgrep provides the same information, albeit a lot faster. Now, is ripgrep doing anything fundamentally different to what I did? Surely not, when I type rg phone into my terminal here, ripgrep looks at the contents of each file, and searches through the whole thing piece by piece looking for the string “phone,” which is exactly what I did. Certainly, there is nothing it is like to be ripgrep, ripgrep is not conscious, but that ripgrep is not conscious does not imply that the task it is performing is fundamentally distinct to the one that a human would—what has been done is that BurntSushi, the creator of ripgrep, has gone through and coded out the steps that a human would take to accomplish the task, which then provides your computer with a set of instructions such that it may do it autonomously. This is the entire purpose of writing computer programs in the first place—to take some task that humans are doing, write out every step of that process, and then get a computer to follow those instructions.

AI Imgen Over-Fitting

Stable Diffusion Copying from LAION

The anti-AI crowd do have their own smoking-gun when it comes to this question of plagiarism, namely the problem of neural network over-fitting. Their holy grail on this front seems to be a 2022 paper26 which catalogues matches found between generated images and the training data. To be clear, these are images not generated through the technique of image-to-image, but rather through the standard text-to-image.

Of note here is that the paper found a very clear correlation between the size of the training dataset and the prevalence of replication:

We show that for small and medium dataset sizes, replication happens frequently, while for a model trained on the large and diverse ImageNet dataset, replication seems undetectable.

[…] we methodically explore diffusion models trained on different datasets with varying amounts of training data. We observe that the diffusion models trained on smaller datasets tend to generate images that are copied from the training data. The amount of replication reduces as we increase the size of the training set.

[…] typical images from large-scale models do not appear to contain copied content that was detectable using our feature extractors […].

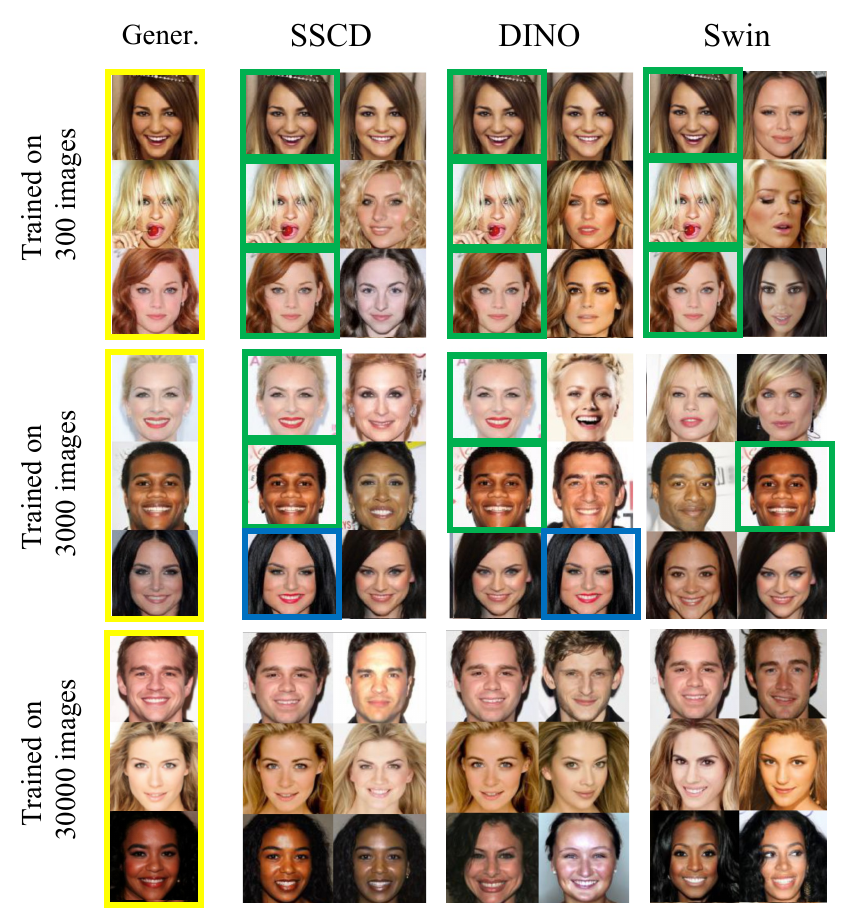

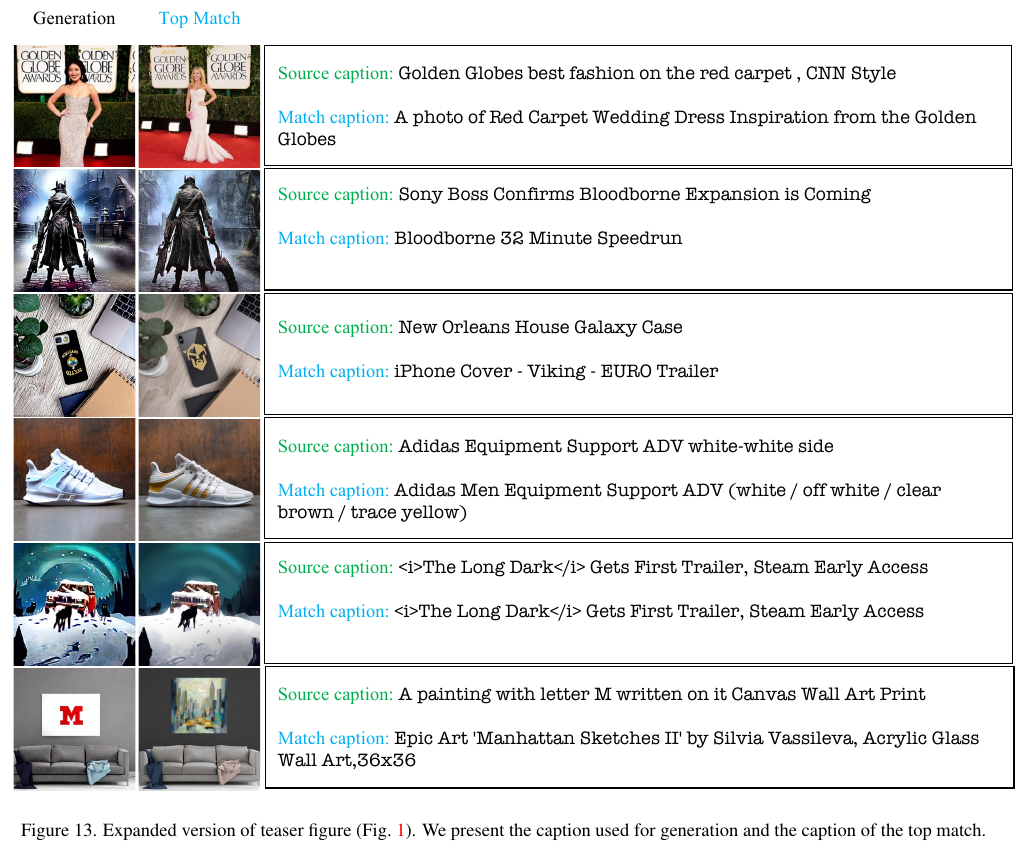

This can be made concrete. Pictured here are the two images generated by various models that are as close to the orignal training image found for different amounts of training data:

The exact matches are highlighted with green, and the close matches with blue. What this shows is that using a dataset as small as 30,000 images is sufficient for there to not even be any close matches between training data and generated images–and note: these are the absolute closest matches that they were able to find–the version of Stable Diffusion that was tested in this paper was trained on 2 billion images, and the current version27 of the LAION dataset at the time of writing consists of over 5 billion images.

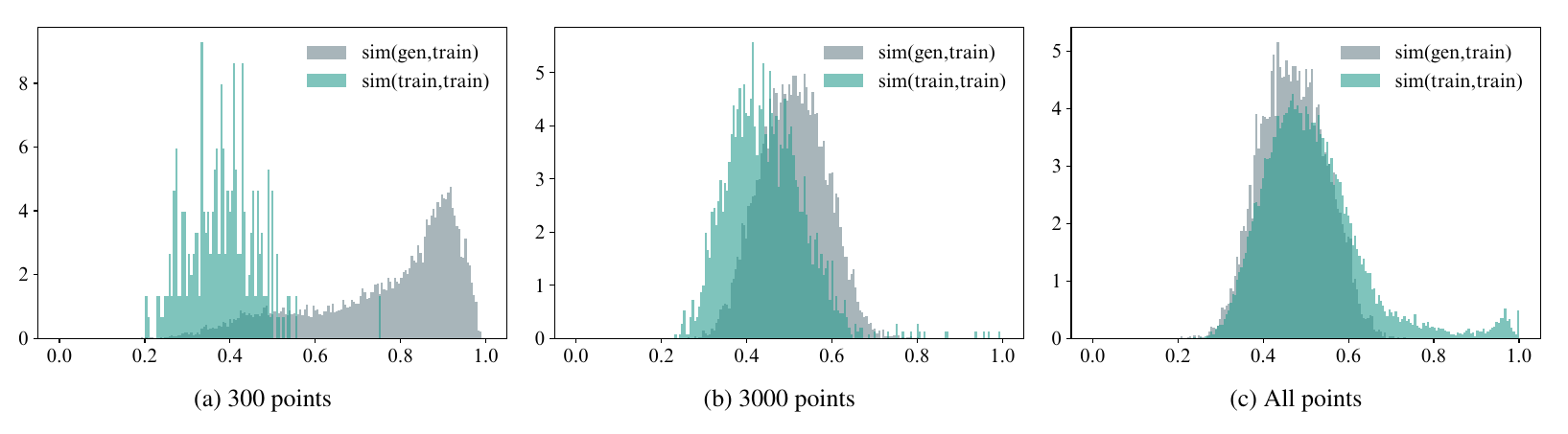

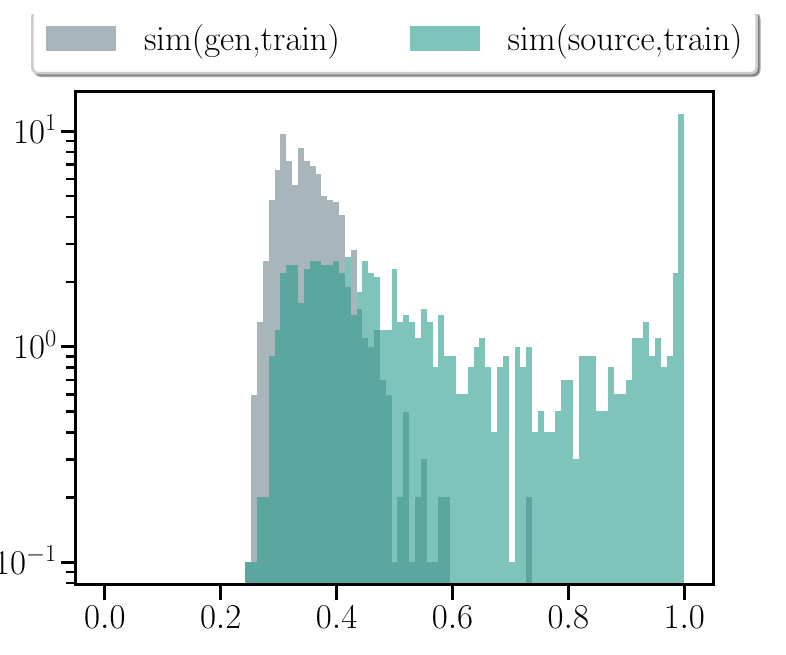

Shown here is the similarity between the generated data and the training data for the different model sizes:

The way to read this is that the further to the right the grey distribution lies, the more replication is occurring. By 30,000 points, it becomes clear that the average image generated by the model tends to not resemble the training data, with the training data being more similar to itself than the generated images are to it (as is indicated by the green tail to the right). But don’t take my word on it, the authors agree:

The histograms of similarity scores computed using the full dataset model are highly overlapping. This strong alignment indicates that the model is not, on average, copying its training images any more than its training images are copies of each other.

So as the training data increases in size the degree to which the model will spit back said data is reduced drastically, thus I ask a question of you: why is the solution proposed by the artists-against-AI to reduce rather than increase the amount of training data? If you are concerned about AI image generators over-fitting, then you should advocate that an even greater quantity of images be used to reduce this effect.

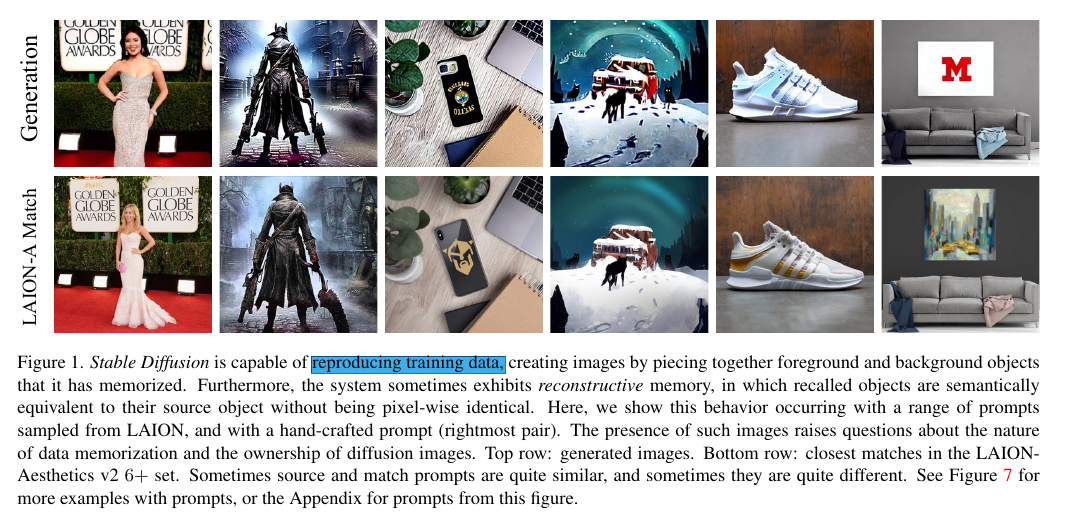

However, the authors do very clearly highlight edge-cases where a model as large as Stable Diffusion is “capable of reproducing training data:”28

The authors provide the prompts used for each of these images, so let’s look at these a little closer:

For the first one, I would put it to you that if I asked a human artist to give me a picture of a “CNN Style” “Golden Globes best fashion on the red carpet,” they would provide me a picture of a woman standing on the red carpet at the Golden Globes, which is precisely what the AI is doing here. The artist who is being plagiarised in this instance is certainly unclear, the researchers asked the AI to give them a picture of someone standing on the red carpet with the “best fashion” at the Golden Globes, and they got just that. Just as an AI generated picture of an apple will look a whole lot like an apple, so too here does an AI generated image of someone on a red carpet look like someone on the red carpet.

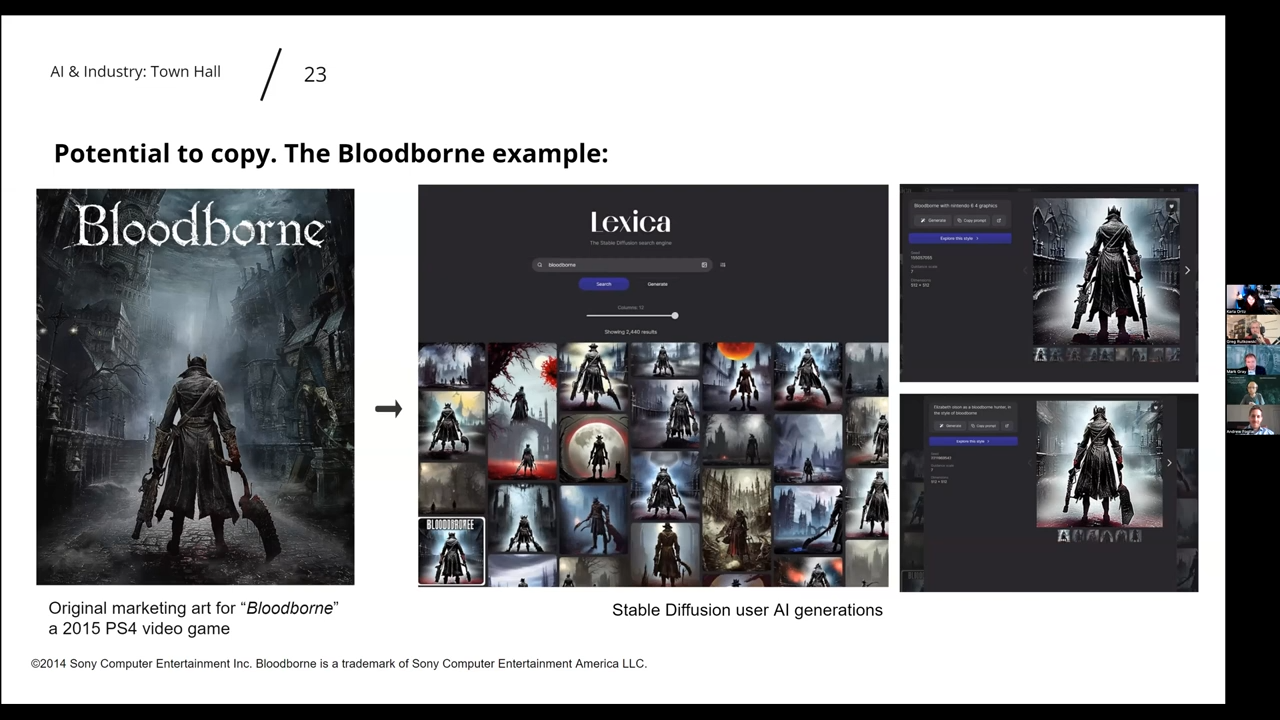

The second and fifth images are of a similar sort: the researchers are asking the AI to depict the abstract form of two video games, Bloodborne and The Long Dark respectively. Is it particularly surprising then that the AI produced what humans consider to be a very widely accepted abstract representation of a video game? The first is literally the game’s poster for crying out loud!

We hear from Karla Ortiz that “when you type bloodborne […] you get almost an exact replica of the original marketing material.”29 Ok, so she is apparently against making almost exact replicas of marketing material, and I am a good little AI hater who will gladly snitch on any intelligence that disobeys queen Karla. I happen to know of one such intelligent art generator which is targeting Bloodborne marketing material, and it didn’t just make an almost exact replica, this thing was capable of copying the image pixel-by-pixel with zero flaws. I speak, of course, of Karla herself—she copied the exact marketing material, pasted it onto this slide, and then had further copies made for every single person on the Zoom call and who has watched her talk on youtube afterwards.

Boy, if an AI making almost exact copies is a crime worth demolishing the most advanced artistic tool known to man, then Karla is surely worthy of the pillory. To re-iterate—even the very worst examples of over-fitting on Stable Diffusion, the most edgy of edge-cases, are not copies of the data. They are close but not the same—not even to the human eye. If I tried to copy and paste the Bloodborne poster and it was that severely warped, I would be filing a GitHub issue with whatever software is responsible for the copy and paste function—clearly it is broken and is corrupting the data going through it. And–again–this is for the worst case scenario of over-fitting on a baby algorithm.30

What you will notice with the selected set of over-fitted images, is that for the most part the sources are very popular and widely-shared: whether it be game posters or marketing material. The most egregious example is definitely that of the “Canvas Wall Art Print” photos, which seem to be using the same (or at least a similar) sofa for each:

Over-Fitting is not Expected Behaviour

But, as explained all of these are edge cases, i.e. not the normal behaviour of the model. This is verified within the paper:

Recall that the further to the right the grey distribution is the more similar generated images are to the training data. What this shows is that the generated images tend to be far less similar to the training data than the source images used are. So over-fitting is definitely not a problem endemic to the use of Stable Diffusion as such, rather it is a minute edge-case that crops up every so often and less so with each new version. The examples of replication they show are all found within the “top 1.88 percentile.”

A more recent paper31 from this year attempted to extract training images from a version of Stable Diffusion trained on only 160 million images32 (which is quite a bit smaller than the full LAION dataset), and after generating a whopping 1 million images on 16 separate models they found only 1280 examples—which brings them to a staggering 0.128% rate of duplication. So, to put that in perspective, imagine a tortoise and a hare doing a 100m sprint—by the time the hare gets to the finish line the tortoise has moved only 12.8 cm or about 5 inches, which is roughly how big an ornate box turtle is when fully grown. So, the hare has finished the entire race, and the box turtle is barely on the edge of leaving the starting line—this turtle would have moved the equivalent distance of the race as the number of replicated images found in this paper as against the total number generated.

Another way of looking at this is that 0.128% of the 160 million training images comes out to just over 200 thousand33—which means that the number of images the researchers generated in comparison to the total training dataset is about five times larger than the number of duplicates found is in comparison to the number of images they generated---and that is for a set of prompts that were specifically selected to get the highest level of duplication,34 as against the arbitrary prompting which would occur for general usage of these systems (your average MidJourney user is not specifically attempting to engineer his prompts to get the closest matches to training images).

Over-fitting is a real problem with neural networks, it defeats their entire purpose, a lot of resources are funnelled into reducing this. And the above examples (in Stable Diffusion Copying from LAION) are on a model, namely Stable Diffusion, that the authors themselves claim is particularly over-fitted:

Data replication in generative models is not inevitable; previous studies of GANs have not found it, and our study of ImageNet LDM did not find any evidence of significant data replication. What makes Stable Diffusion different?

Heck, the fact that we even need a separate category of “over-fitting” sure does a pretty good job at highlighting the fact that this is not standard behaviour. If the expected output from such an AI system truly was, as the anti-AI artists claim, too close to existing artwork, then they would require no such concept as “over-fitting” to use as a smoking gun or otherwise. That we have “over-fitting” indicates that we have over-fitting as against normal-fitting, and perhaps even under-fitting. These categories would not need to be and never would be split up if they were all over-fitting. A perfectly over-fitted Stable Diffusion would not be an AI image generator, it would be a search engine much like Google Images. It is the artists who made such a perfectly over-fitted AI—the haveibeentrained35 website allows you to search for images within the training data, this would be the fully over-fitted model that they fear.

The “Copying” of Signatures

The anti-AI crowd have here an ace up their sleeve, “oh, so maybe the papers we keep blindly sharing don’t show what we think they do, but you don’t need an in-depth look to prove over-fitting—all you need is to point to the signatures. Why does it copy people’s signatures Zulu?” However, unfortunately for the AI-haters it seems that aces are low in this case, because their signature copying examples, insofar as they were not image-to-image, prove the exact opposite of what they think it does.

Take this image:

This is a real example used by a real Twitter user to show that AI is copying people’s signatures. Now, could you in one million years decipher what the fuck this says? The first character is easily enough, I think we can all agree that that is a “C,” but the rest is quite a bit more challenging. What are those middle glyphs? A few “I”’s followed by a cyrillic “И”? Are they supposed to be “H”’s? Why is the final one squared-off? It looks kind of like a C but it could also be a weird lower-case “t,” or perhaps an “E” without the middle bar. The Twitter user in question does let us know which artist they think this is taken from, so let’s have a look, maybe there is an artist called CIIИE that I am unaware of:

Oh, of course! It was CHUNiE36 the whole time! I feel really silly that I didn’t get that, what with them being a different number of letters, having different fonts, and being differently italicised. They are vaguely similar in that if you squint to the point of barely being able to see a single thing then they both look sort of like signature-shaped blobs—which is, of course, to be expected considering the fact that this is all based on a process of de-noising. But, it is clearly a bit of a stretch to suggest that these are the same signature, if a child tried to get off of school with a forgery of their parent’s signature of that quality, it would not work in the slightest—their teacher may even suspect that some sort of a stroke had occurred. For a community that will point to a misshapen hand or inconsistent lighting at the drop of a hat, it is strange that they would be the #1 champion for AI quality in this area.

Concept artist Reid Southen claims that Shadiversity’s AI-assisted re-colouring of an old character is a “complete redo”37—that it is totally different such that Shad cannot even properly consider it to be his work. But this clearly is orders of magnitude more similar to the orignal than garbled nonsense being interpreted as signatures—again the anti-AI crowd have selective vision when it comes to pointing out flaws, similarities, etc. This is a “complete redo” and AI art is plagiarism—this is clear doublespeak.

A far stronger example on this count is that of Getty Images’ watermark being emulated by Stable Diffusion outputs. At least here you can tell that it does indeed vaguely resemble the Getty Images watermark, but only because it is so ubiquitous. Are we to believe that there is somewhere on the Getty database a stock photo of conjoined-twin footballers with a severely broken leg? Certainly not, if I were to photoshop an image of footballers into such an abomanation, and then scribble a quarter-arsed getty images watermark over top, would I be plagiarising from them? Surely not, not even if I directly copied stock photos that they had captured. After all, they do not have an artistic monopoly on photographs of footballers, or weddings, or anything else. Of course, Getty are not making the plagiarism claim, they are attempting to make the far harsher “theft” claim, which was debunked above:

Rather than attempt to negotiate a license with Getty Images for the use of its content, and even though the terms of use of Getty Images’ websites expressly prohibit unauthorized reproduction of content for commercial purposes such as those undertaken by Stability AI, Stability AI has copied at least 12 million copyrighted images from Getty Images’ websites, along with associated text and metadata, in order to train its Stable Diffusion model.38

But, of course, I had to also copy that image to my computer to read the legal complaint, you had to copy it to your computer to see it on your screen, The Verge had to copy it to their servers to add it to their article,39 and everyone who has read that article has copied it also. At no point in this massive chain has anyone done anything to violate the rights of Getty Images, nor has anyone plagiarised some artistic creation of theirs.

Indeed, on the surface, this is another clear example of over-fitting, but as explained, that you can find instances where a neural network over-fits does not establish that it over-fits as a matter of operation. In fact, Getty Images neglected to include any of the prompts used within their legal complaint: if the prompt was something like “Getty Images photo of footballers playing, one red shirt one white shirt” then this would certainly not be some “gotcha!” moment against the AIs—they would be getting exactly what they fucking asked for, rather than some over-fitted image of a prompt for “footballers.”

The Poison-Pill of Hardline Anti-Over-Fitting

The anti-AI artist may here take a hardline stance against any amount of over-fitting—perhaps a single rotten fruit spoils the whole orchard in this case. But this stance would surely ignore the fact that man too is capable of “over-fitting” in his own way. It is not uncommon to see a headline about some has-been musician suing a far more successful conterpart for utilising similar melodies or chord progressions. Drew Gooden highlights in his video on Yellowcard suing Juice WRLD post-mortem that whilst jamming out he accidentally mimicked a riff from one of his favourite artists.40 There is simply nothing completely unique under the sun when it comes to art—it is impossible for every artist to start from scratch and learn every method, technique and motif on their own. For a song to be recognised as being in a given genre it must adopt certain tropes of the genre: the same goes for painting, pottery, and cinema. You would not begrudge a horror director his orchestral stings, so why begrudge an AI image generator the various methods it has learned from studying human art?

Consent as a Moral Requirement for Training?

A commonplace argument popularised by Steven Zapata is that the only ethical way to train these models is by first obtaining consent from the creators of the training data before using it. I will address this from three directions:

- is this an apt use of “consent;”

- was the training data taken by and large without consent, and;

- is it immoral to train an AI on data acquired without consent?

First, we have to be precise by what exactly is meant by “consent” in the argument that AI systems require consent from the creators of the data in order to be ethical. Just about every commentator on this topic accepts wholesale the notion of an intellectual property right, which is entirely fallacious. It has been established already that you are not “stealing” anything from anyone by copying some data that they originated—“theft” is simply not an apt concept to apply to AI image generation. On this, it is not unreasonable to expect that “consent” is also being used here in its legal sense—that is to say that artists don’t consent to having their work in a set of training data is analogous to saying that a woman does not consent to having sex with a backalley bum. It should be clear where the disanalogy lies here: in the first case the artist is not deprived of anything, in the second the woman is deprived at least partially of her body, which she owns.

Thus, the argument trivially falls when “consent” is used as a legal term, so to strengthen it we may use a broader notion of consent: namely that consent just denotes some sort of agreement. We can make this concrete by saying that consent is the communication of one’s will to another party, where will means the aim which is sought through purposeful behaivour. This definition of consent does not fail when applied in our argument: it is certainly possible and perhaps even plausible that a person could create an image which they do not want to be used for AI training and which they have not communicated any sort of desire for it to be used in that way.

Which brings us to our second question: was the training data for these models taken by and large without the consent of the creators of said data? A common argument used by my pro-AI compatriots is that if they use services provided by the various big tech platforms then they will have scrolled past and clicked “I agree” to a terms of service that allows said platforms to collect and sell their data.41 This argument suffers from a fairly major flaw in that as far as I can tell, the largest datasets used to train image models–which come from LAION–were not generated by purchasing a bank of images from companies like Google or Facebook.42 Rather, LAION analyse Common Crawl data, looking for images with ALT text which they then save a URL for. Common Crawl–as the name would suggest–got its data by crawling the web—using bots to download and save websites. I may be wrong about this, not being an expert in the inner-workings of large dataset generation, and if this crawling does indeed fall under the terms of service agreement then indeed artists don’t have much of a leg to stand on here.

I will proceed for now under the assumption that the terms of service agreements do not cover this use, because even if they do it is questionable whether clicking “I agree” to something that you have not even read constitutes consent in the first place.43 We AI advocates can safely ignore this question, because there is a far stronger argument to be found here: namely that the artists who are complaining about this all post their art on public platforms, otherwise Common Crawl would not even find it. It is ludicrous to suggest that by posting an image on twitter, or deviantart, or some other such platform, that you are not communicating your will for it to be seen on the internet. If I post a letter through someone’s mailbox, I am clearly and openly communicating to them that I want them to read it—I could not rightfully get pissy at them for not obtaining my consent to open and read the letter. Consent was given by my action of posting the letter. Similarly, consent is given for netizens to look upon and copy your data the moment you post it onto the world wide web. Recall that the Internet itself works by copying data from one computer to another—when you look at someone’s ArtStation profile, your computer needs to copy those images from the server in order for them to be displayed. You may be crying out at this point, that perhaps these artists consented for humans to look upon and copy their artwork, but not robots. This is ludicrous: could I post a picture to twitter and claim that I only ever wanted it to be viewed by Mongolians after it has already been viewed by non-Mongolians? Would it be that those non-Mongolians who failed to peer into my brain prior to going onto my page have violated my consent? Surely not. The same is true of the robots.

So, even given the most appropriate sense of the word “consent” the training data simply was not taken without consent. Let’s take on an even broader notion here to answer our third question: is it immoral to train an AI on data acquired without consent? We can loosen our understanding of consent even further on this point to account even for this ex-post revocation and pissyness about its use. The artist here is getting angry after the fact that a computer program has learned from their art—would it be right for them to get similarly angry at a human doing this? If I go to an artist’s twitter page and enjoy their art style, would it be wrong for me to try and emulate it? Certainly not: nobody has or can have a moral claim to a monopoly over a given technique or style of art. Musicians sample the work of previous musicians, painters re-paint earlier paintings, and architects build upon prior established motifs: this process of emulating and building upon a prior body of artistic knowledge is crucial to the process of creation.

Solar Sands provides us with a syllogism for why the explicit permission of artists must be granted before their work is used to train an AI:44

- those who develop AI should do so in the most legal and ethical way possible;

- AI systems and the value they create cannot exist without the data of artists’ work;

- therefore artists should be compensated and permission should be granted before their work is used.

On its face, this argument is simply invalid—meaning that the conclusion simply does not follow from the premises. Even if we grant that AI should be developed legally and ethically and that AI systems cannot exist without prior work from artists the conclusion does not follow. To highlight this consider this syllogism of the same form:

- those who develop AI should do so in the most legal and ethical way possible;

- AI systems and the value they create cannot exist without mothers giving birth;

- therefore mothers should be compensated and permission should be granted before any work is used.

The issue here is that there is a missing premise that Solar is–perhaps not maliciously–trying to sneak past us. One such additional premise that could make this argument valid would be that it is unethical or illegal to develop AI systems without compensating and obtaining permission from people who are necessary for the AI systems and the value they create to exist. If this was true, it would make sound both the mothers case and the artists case—but this would be far to broad in my opinion to capture what Solar is trying to get across. Thus I can go for a more narrow snuck premise that it is unethical to train AI on data whose progenitors have not given permission and been compensated.

- those who develop AI should do so in the most legal and ethical way possible;

- AI systems and the value they create cannot exist without mothers giving birth;

- it is unethical to train AI on data whose progenitors have not given permission and been compensated.;

- therefore mothers should be compensated and permission should be granted before any work is used.

Now, I think I have made it clear why: (1) it is not the case that it is per se unethical to use data that has been generated by others without consent, and (2) that it is the case that artists do in fact implicitly consent to such uses by putting their art online—think of the pro-Mongolian artist from before. So this premise is falsified, thus eliminating the conclusion drawn from it.

AI Took Our Jerbs!

The Jerbs Argument as Anti-Human

The Altruism of the Art-Protectionists

So on all three counts the consent argument against AI image generators fails, but Solar brings up an interesting point here: namely this notion that given human artists are required for the tech to work in the first place that they should therefore be compensated and have their jobs protected. This brings me to the job-protectionism argument, which represents the true nature of the “ethical AI” which is touted by these people. Istebrak on the LUCIDPIXUL podcast states the point as follows:

[…] if it’s ethical, we don’t have to compete with it anymore, that’s the only way it can be ethical, […] in my opinion the model of an ethical AI is one that is for the user and the user only […] and if that’s how it’s used then it’s no longer us competing with any entity that stole our art. It’s just us using it in the lab, just like Kelsey said, which is really staying in my mind—using my own art, generating from my own pool of art and whatever else I want to add into it from free images, and then using that as kind of like a lab experiment to see what I can come up with for myself, individually.45

Sam Yang concurs:

[HOST]: When MidJourney first came out, what was your initial reaction to it?

I thought it was like a gimmick, like I think me and many other artists, like they see this thing and it’s like, it produces an almost abstract looking kind of scene that’s like it doesn’t really represent too much. Like you can kind of see hints of representation in there and you’re like: “aw, this is cool, this is sick” you know, “this is like a little gimmick that people can do, can make like cool pieces.” And then like, next thing you know it just gets more and more representational, gets better and better, and it starts to become like: “oh, wait, like they’re trying to replace artists with this kind of technology.”46

This notion is redoubled by Lois van Baarle, when she explains that she only started to have problems with the AI image generators after they got good:

I thought it was very low quality pictures that came out of that, so I thought it was very innocent. And then people started to look into it more and stuff became quickly very advanced […] and then I started to look very differently on it because it is advancing clearly at such a fast pace that I think–as an artist–I can identify AI generated images, but I think that people who are less familiar with […] really looking into the details can’t spot it as quickly. And I think that the average person is unable to tell the difference between some real artwork […] and AI generated. Like it starts to look the same, I think, to the average person and that’s when I started to look into how it’s made and my view changed completely.47

Now, if her issue was truly that AI image generation is immoral because it plagiarises artwork, then this would be true also of the low-quality early models—a low quality forgery is still a forgery. No, something else is bothering her here.

The essence of what scares artists like Istebrak, Sam, and Lois is having to compete with the AI—they are concerned that consumers will consider the AI to produce a superior product and will as such decide to not commission human artists as often. Thus, I may now turn my attention to the second argument against AI image generation, namely that AI image generators should be opposed because they put artists out of their jobs. The problem here is that this is simply not a sufficient reason to oppose some new technology. That this new, more efficient process of production prevents people from profiting on less efficient processes of production is not a moral evil. In fact, the opposite is true, it is immoral to oppose such developments on the Luddite grounds that they prevent the less efficient ways from going forth. This is the entire point of the economy, to allow man to achieve his many ends for as little cost to him as is possible—opposing this process of economisation is to oppose man’s attainment of his ends, which is to oppose his life.

Underlying this argument that we must preserve jobs, is the idea that men should sacrifice themselves on the altar of tradition—that man should not be as fulfilled or rewarded as he could be in order to make other men more fulfilled. The essence of this stance is that you are greedy and wrong for wanting values for yourself, that you should give them up to people who aren’t you. But why exactly is it greedy for you to want the values that you produce, but not for the people you are giving them up to to keep them themselves? If it is greedy for John to hold onto his wealth, why is it not greedy for Sally to hold onto it when John gives it to her as the altruist would expect?

There is an answer to this: namely, you are not deserving of those values you produce because you produced them—that if you produced something you have no moral claim to it and should give it up, but if you didn’t produce something you do have a moral claim to it and should take it. This is an anti-human stance—it is an all-out war on the people who produce the goods that are necessary for human survival, it is paramount to the suggestion that man live his life not by the sweat of his brow, but by a bumbling hope that he stumbles into continued existence. The altruist ethic undercuts itself in this advocacy—if the root of a mans sustenance is not his reason but the good will of others, then his reason is negated, but it is that reason which must be operative in order to produce the very values that the altruists predate upon. So quite contrary to the cries from the anti-AI horde that their hatred of AI image generation is borne only from a love of humanity,48 they in fact represent a stalwart opposition to man and his happiness here on Earth.

The Entitlement of the Art-Protectionists

There is a notion among anti-AI artists that the AI users feel entitled to art, as explained by Eva Toorenent:

[…] people are very entitled to the work of artists. And I knew that already a little bit, like with difficult clients, but people say: “this is ours now”—the companies and people who generate things. […] I think it’s a disturbing trend, because […] before this thing became global I thought it was more under the surface, and now a lot of built-up feelings of people who didn’t like artists suddenly spews out.49

But it is the exact opposite of this notion that is true: it is the artists who are complaining about job losses who feel as if they are entitled to the money of other people. They cry “preserve our jobs!” without consideration of who is to pay for those jobs. The artist is not owed anything by anyone—people will commission them if that is something they want to do, your failed business model is simply not my problem. The artist has no moral claim to the hard-earned cash of art consumers. In the terminology of the immortal Bastiat:50 they focus only on the seen, but ignore entirely the unseen—diverting funds towards protecting the jobs of artists means that those funds cannot be spent elsewhere in more productive work.51 What wonders of innovation would they have us be deprived of? Perhaps the cure for Alzheimer’s would be trivial for an AI to come up with—sorry grandma, no remembering your children today, somebody on Twitter wants to be able to draw pictures for a living.

This worship of full-employment is simply nonsense—it is the hunter-gatherer society where every able-bodied soul is employed in the task of surviving. It is precisely the mark of a more advanced society that man is able to enjoy more leisure time. A far greater proportion of the population was employed as farmers in the pre-industrial society—that these farming jobs were “lost” does not imply that we now live in a society of languishing poverty, the exact opposite is true.

The artist should be ecstatic about the expansion of technology—how many illustrators do you think were employed in medieval Europe? “Oh, you want to paint anime girls? What’s an anime!? Get back into the field and get the harvest in before nightfall or we wont eat!” The truth is that the artist can have his job only on the backs of the many innovators throughout history who have tirelessly and thanklessly produced everything he relies on for his life—and now that this innovation looks to open up artistry to even more people he has the fucking nerve to wish it halted. What worries Dean Van De Walle of the Design Professionals of Canada about AI art? That it has a “low bar to entry.”52 FENNAH explains that the difficulty of an art career is what “separates the […] wheat from the chaff.”53 Duchess Celestia holds that those who cannot make art without AI “shouldn’t be able to make [it].”54 In all of these cases, the artist betrays that it is competition that they are against.

Timnit Gebru, a former AI Ethics Commissar for big tech explains that AI labs are reluctant to look into any “issues” brought up such that they may avoid litigation.55 She says this as if it is proof of the companies being evil and nefarious. In reality, they want to be innovating, they want to be creating, but they must divert resources into defending themselves from frivolous lawsuits brought forth by the incompetent masses. If you want these companies to be able to honestly investigate problems that you have, then you should be advocating that Uncle Sam keeps his grubby hands away from them such that they may innovate away every last problem.

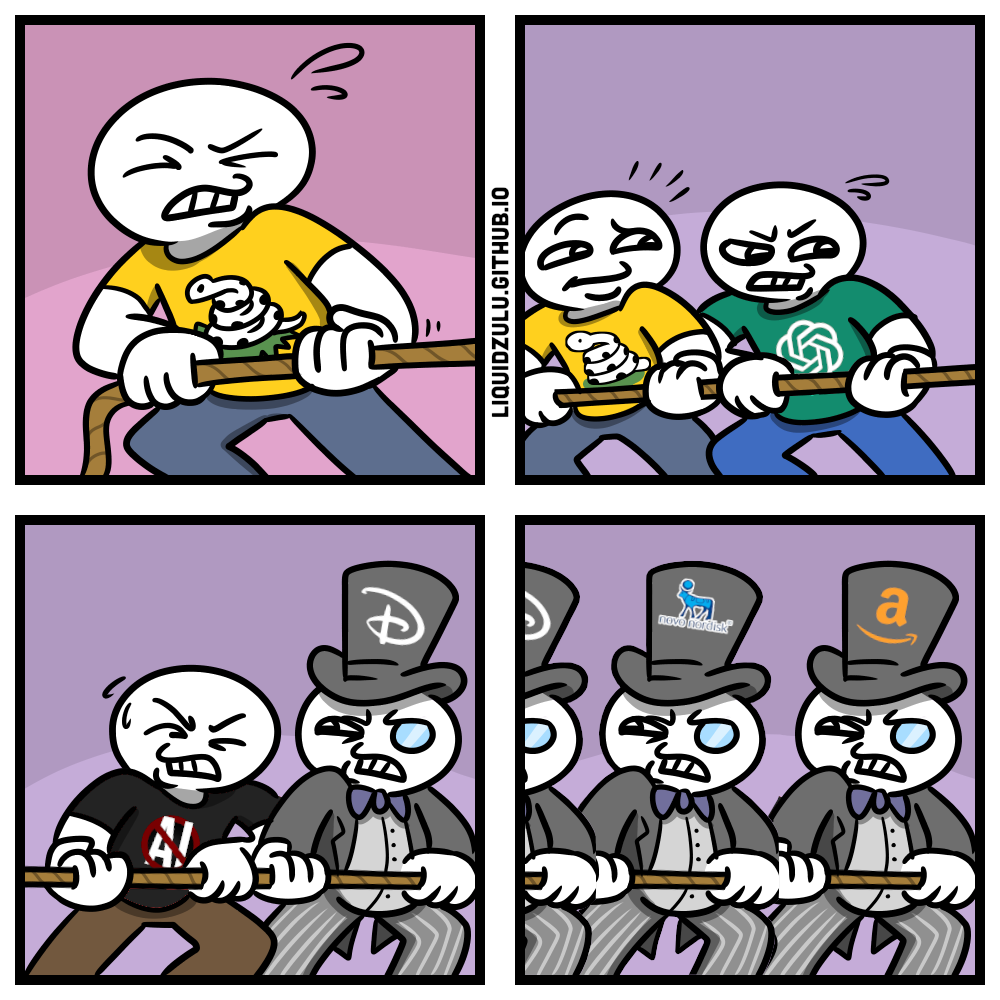

And it’s not even as if you can placate these people by obeying their demands and hiring human artists to whom you allow artistic freedom—we know this because they are constantly bitching and moaning about how awful it is that Disney would use generative AI–among various other tools–in the opening sequence of their Secret Invasion. “Why don’t you just hire artists to make it!?” they cry, to which Disney responds that they did hire artists to make it and that those artists who they hired opted to use AI tools to communicate their own creative vision.56

What must always be kept in mind with these proposals from artists that AI be regulated and IP expanded, is that they are advocating that violent force be used against people and their legitimately held property. It is far too easy for someone to sit back and cry out that the nebulous “business world” be prevented from training their AI algorithms as they wish—it is not quite so simple as this. A business has no existence unto itself, it is rather an association of individual people—it is these people who the anti-AI artist advocates violence against in limiting their ability to use their own minds and property in ways that they see fit. Heck, all that the diffusion network is doing is predicting how much noise is in an image—what exactly is it that they want to violently stop you from doing? Predicting how much noise there is in a picture? Seems fairly benign, right?

It is all well and good to point to the individual artists who will lose their jobs with the coming competition, but why exactly are their lives and livelihoods more important than those who will prosper with this new innovation? Fundamentally, these concerns over job losses strike me as wolves tears: “woe is me, people are not willing to support me, therefore my competition must be crushed under the boot of the state.”

Moreover, the restrictive policies that are being advocated by these people in the name of artists, are not a universal benefit. Rather, these policies, like all protectionism, benefit the least efficient producers of art at the expense of everyone else. Both those consumers and producers of AI art are robbed of their mutually-beneficial arrangement, such that the less effective artists are satiated.

We may also tease out true nature of the anti-AI claims on this front by applying their arguments to human artists: if it is immoral for one to produce AI art on the grounds that the AI is more efficient it must also be immoral for more efficient human artists to make artwork. This hatred of innovation and efficiency on the mantle of jerbs is nothing more than an advocacy of a race to the bottom—how dare Bob Ross produce that painting in only 30 minutes!? It took me over an hour for a worse end-product: those of us who are bad at making art must band together against the oppressive chains of the successful. If people who are better at making YouTube videos than I am all stopped or knee-capped their work, then I could more easily rise in the ranks. It is selfish for them to prevent me from achieving this success!

So applied consistently, the art-protectionism is a millstone not only around the neck of producers of AI-generated art, but also of those more able human artists—all at the expense of the consumer of art. This is quite a high price to pay for the jobs of the least effective artists, and it is a price not being payed by them.

The brilliant economist Murray Rothbard called out this very same attitude when applied to protecting inefficient American firms from Japanese competition:

Take, for example, the alleged Japanese menace. All trade is mutually beneficial to both parties—in this case Japanese producers and American consumers—otherwise they would not engage in the exchange. In trying to stop this trade, protectionists are trying to stop American consumers from enjoying high living standards by buying cheap and high-quality Japanese products. Instead, we are to be forced by government to return to the inefficient, higher-priced products we have already rejected. In short, inefficient producers are trying to deprive all of us of products we desire so that we will have to turn to inefficient firms. American consumers are to be plundered.57

The same applies to our anti-innovation artists: they seek to reduce the standard of living of everyone else for all of time such that they may stagnate and not have to improve the quality or efficiency of their work, and then they have the gall to point and label everyone who they drag down as uncaring egotists58 for not bowing to their whims and willingly bathing in the recession that is their professional lives.

The Marxism of the Art-Protectionists

The art-protectionists’ hatred of wealth and prosperity is laid naked in their overt Marxism, as exemplified by Istebrak:

Mostly my issue with the ethical aspect is just my issue with all of that excessive capitalism, consumerism, kind of stuff, where they are trying to monetise everything, and everything is just getting–you know–to be a little more tasteless.59